Valentine's Day.

Seth Mulliken

11

Looking at the modern, commercial Valentines Day – replete with red hearts, Cupids, cards and flowers – it is easy to forget at times that the 14th of February is actually St. Valentine’s Day, so named for the Roman saint of the third century AD who was summoned before the Emperor, Claudius II. There he recounted himself so well that the Emperor took a liking to him and noted how wisely and correctly he spoke when talking of God. Functionaries in his court, however, worried about the influence that Valentine was gaining with the Emperor and warned that he was being lead astray. This resulted in a hardening of the Emperor’s heart and he turned over Valentine to a prefect for punishment. There he was, through the power of prayer, able to restore the sight of the prefect’s blind daughter and the entire house was converted to Christianity. As a result of this, the Emperor ordered Valentine beheaded around the year 280.

This version of his life, recounted in Jacobus de Voragine’s thirteenth century Legenda Aurea, says nothing of the connection between St. Valentine and lovers, concentrating instead on his spiritual strength as a martyr. Yet in the fourteenth century Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules, created for the betrothal of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia, states that the events of the poem occurred “on Seynt Valentynes day, / whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make / of every kinde that men thinke may” ([it] “was on Saint Valentine’s day / when every bird came there to choose his mate / of every kind that men may think of”) (l. 309-311). The Oxford English Dictionary states that this is the first reference of St. Valentine’s Day in connection to lovers, a distinction that has led many to assume that Chaucer invented the connection between the two for the sake of the poetic conceit he was setting up.@"Valentine, n.". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 11 February 2014 http://www.oed.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/view/Entry/221141?rskey=kh1Liy&result=1&isAdvanced=false. For further information on the connection between Chaucer and Valentine’s Day, see Henry Ansgar Kelly’s Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine (Leiden: Brill, 1986).

The connection between St. Valentine’s Day and the day birds select their mates also appears in the prologue to Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women (l. 138-146), in Le Songe Saint Valentin by Chaucer’s contemporary and fellow servant of John of Gaunt, Oton de Graunson, and in two poems in John Gower’s Cinkante Balades. Many of the elements we associate with Valentine’s Day today – specifically the use of the pagan god of love Cupid – are also referred to in these poems, which in turn have a connection in both style and substance to the mid-thirteenth century Roman de la Rose.

It is possible that the St. Valentine mentioned by Chaucer actually had a May feast date, which would be more appropriate when the connection to the mating season of birds is considered. However, since there have been twelve saints named Valentine and three of them were supposedly martyred on the 14th of February, it is likely that a conflation of their individual legends created a composite Valentine in the minds of worshippers. Chaucer was then able to appropriate this composite saint for his poetic work and leave the particular feast day ambiguous. It is clear however that by the late fifteenth century that the Saint Valentine spoken of in the Legenda Aurea has had his legend expanded to include the romantic elements that Chaucer connects to him. The marrying of Christian couples – the attribute most connected to the bird’s selection of mates – becomes one of the reasons for St. Valentine’s arrest in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle. The Chronicle’s woodcut of the Saint is also supposedly the first depiction of Valentine, but as we will see there was at least one earlier depiction.

In honor of the day, we at MESA have selected a number of images from our collection – some religious, some fanciful, and some bawdy – to illustrate the many ways in which people of the middle ages chose to represent and honor love and the saint who came to be associated with it.

This version of his life, recounted in Jacobus de Voragine’s thirteenth century Legenda Aurea, says nothing of the connection between St. Valentine and lovers, concentrating instead on his spiritual strength as a martyr. Yet in the fourteenth century Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules, created for the betrothal of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia, states that the events of the poem occurred “on Seynt Valentynes day, / whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make / of every kinde that men thinke may” ([it] “was on Saint Valentine’s day / when every bird came there to choose his mate / of every kind that men may think of”) (l. 309-311). The Oxford English Dictionary states that this is the first reference of St. Valentine’s Day in connection to lovers, a distinction that has led many to assume that Chaucer invented the connection between the two for the sake of the poetic conceit he was setting up.@"Valentine, n.". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 11 February 2014 http://www.oed.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/view/Entry/221141?rskey=kh1Liy&result=1&isAdvanced=false. For further information on the connection between Chaucer and Valentine’s Day, see Henry Ansgar Kelly’s Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine (Leiden: Brill, 1986).

The connection between St. Valentine’s Day and the day birds select their mates also appears in the prologue to Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women (l. 138-146), in Le Songe Saint Valentin by Chaucer’s contemporary and fellow servant of John of Gaunt, Oton de Graunson, and in two poems in John Gower’s Cinkante Balades. Many of the elements we associate with Valentine’s Day today – specifically the use of the pagan god of love Cupid – are also referred to in these poems, which in turn have a connection in both style and substance to the mid-thirteenth century Roman de la Rose.

It is possible that the St. Valentine mentioned by Chaucer actually had a May feast date, which would be more appropriate when the connection to the mating season of birds is considered. However, since there have been twelve saints named Valentine and three of them were supposedly martyred on the 14th of February, it is likely that a conflation of their individual legends created a composite Valentine in the minds of worshippers. Chaucer was then able to appropriate this composite saint for his poetic work and leave the particular feast day ambiguous. It is clear however that by the late fifteenth century that the Saint Valentine spoken of in the Legenda Aurea has had his legend expanded to include the romantic elements that Chaucer connects to him. The marrying of Christian couples – the attribute most connected to the bird’s selection of mates – becomes one of the reasons for St. Valentine’s arrest in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle. The Chronicle’s woodcut of the Saint is also supposedly the first depiction of Valentine, but as we will see there was at least one earlier depiction.

In honor of the day, we at MESA have selected a number of images from our collection – some religious, some fanciful, and some bawdy – to illustrate the many ways in which people of the middle ages chose to represent and honor love and the saint who came to be associated with it.

Valentine's Day.

Seth Mulliken

12

This bas-de-page scene, from the Queen Mary Psalter (BL Royal 2 B VII f.242v) illustrates Saint Valentine’s life before the explicit connection to love forged by Chaucer. Here we see Valentine before Claudius II along with a guard or other Roman functionary. What appears in this image to be an arm placed around his shoulder in camaraderie actually represents the guard about to take Valentine away to be beheaded. The next image, f.243r, shows the same figure about to behead a kneeling Valentine.

Although this book is commonly known as the Queen Mary Psalter, it was originally created between 1310 and 1320, possibly at the behest of Queen Isabella or her husband, the English King Edward II. It was created in either London or East Anglia and the text is in Latin with French image captions. As such, it reflects the version of the life in the Legenda Aurea and shows that version had cultural currency in the highest levels of the English court on the eve of Chaucer’s life and literary career.

Although this book is commonly known as the Queen Mary Psalter, it was originally created between 1310 and 1320, possibly at the behest of Queen Isabella or her husband, the English King Edward II. It was created in either London or East Anglia and the text is in Latin with French image captions. As such, it reflects the version of the life in the Legenda Aurea and shows that version had cultural currency in the highest levels of the English court on the eve of Chaucer’s life and literary career.

Valentine's Day.

Seth Mulliken

13

While St. Valentine in the Queen Mary Psalter might be considered to represent love for his fellow man, the concept of courtly love found in the poetry of the thirteenth-century troubadours would celebrate an altogether more worldly representation. While some of these representations of courtly love might be wholly innocent, such as the presentation verses to a lover depicted in the first image, others were much more carnal. In the Roman de la Rose an allegorical world is created wherein the narrator, commonly known as the Lover, attempts to pick the Rose, thus achieving his desire and giving us a lasting connection between flowers and virginity to this day.

The book is written in two parts. The first, written by Guillaume de Lorris, begins with the Lover discovering a walled garden. He gains entrance thanks to the aid of a beautiful woman, and meets a number of dancers who represent allegorical virtues such as Beauty, Generousity, and Diversion. They lead him on a tour of the garden, which eventually ends at a beautiful bed of roses near the Fountain of Love. Overwhelmed with desire to pick a particular rose, the Lover is lectured by Love on how to gain his desire and is aided in his quest by figures such as Warm Welcome, Friend, Honesty, Pity, and Venus. He encounters Danger, Slander, and Fear, overcomes Chastity, and gains a kiss from the Rose.

In the second part, written by Jean de Meun and which these images illustrate part of, Jealousy imprisons the Rose along with Warm Welcome in a castle (seen in the first of these two images, f. 39r of Harley 4425). The Lover in attempting to reclaim her is forced to again battle a number of allegorical figures – and readers are forced to deal with long digressive and misogynistic lectures by figures such as Reason. Ultimately, the Lover calls upon an army to besiege Jealousy’s castle, and the particular image from Douce 195 (f. 152v) presents the culmination of that battle, with Venus setting the castle of Jealousy aflame. The negative allegorical figures are escaping the castle, and in the right hand corner the Lover appears to be reconciling with the Rose.

Chaucer wrote a translation of this poem, of which we have only a fragment, and similar allegorical figures appear in several of his dream vision poems, particularly in the prologue of the Legend of Good Women, where a daisy figures prominently as the representation of the faithful Alceste and several of the allegorical figures from the Roman de la Rose are mentioned. Furthermore, part of the explanation given in the poem for Chaucer’s necessity in writing this poem is because he “hast translated the Romaunce of the Rose”, considered to be a “heresye” against the law of the god of Love (l. 329-330). Interestingly, the “Parlement of Foules” is presented as an example of how Chaucer has assisted Love, and serves as a justification for why the writing of the Legend of Good Women, rather than a more serious punishment, is required of him (l. 415-423).

King’s 322, from which the first image is drawn, is an Italian manuscript of the mid fifteenth century and contains a series of love sonnets written for a Mirabel Zucharia or Zucharina, presumably the woman depicted in the image. Harley 4425, from which the second image is drawn, is a late fifteenth century Netherlandish manuscript in French containing four large miniatures, of which this is the final one. It was originally commissioned for Engelbert II, count of Nassau and Vianden. Bodleian Douce 195, from which the third image is drawn, is richly illustrated with one hundred and twenty five miniatures. Originally produced in France, it was owned by Louise of Savoy, the wife of Charles of Orléans and mother of the French king Francis I.

The book is written in two parts. The first, written by Guillaume de Lorris, begins with the Lover discovering a walled garden. He gains entrance thanks to the aid of a beautiful woman, and meets a number of dancers who represent allegorical virtues such as Beauty, Generousity, and Diversion. They lead him on a tour of the garden, which eventually ends at a beautiful bed of roses near the Fountain of Love. Overwhelmed with desire to pick a particular rose, the Lover is lectured by Love on how to gain his desire and is aided in his quest by figures such as Warm Welcome, Friend, Honesty, Pity, and Venus. He encounters Danger, Slander, and Fear, overcomes Chastity, and gains a kiss from the Rose.

In the second part, written by Jean de Meun and which these images illustrate part of, Jealousy imprisons the Rose along with Warm Welcome in a castle (seen in the first of these two images, f. 39r of Harley 4425). The Lover in attempting to reclaim her is forced to again battle a number of allegorical figures – and readers are forced to deal with long digressive and misogynistic lectures by figures such as Reason. Ultimately, the Lover calls upon an army to besiege Jealousy’s castle, and the particular image from Douce 195 (f. 152v) presents the culmination of that battle, with Venus setting the castle of Jealousy aflame. The negative allegorical figures are escaping the castle, and in the right hand corner the Lover appears to be reconciling with the Rose.

Chaucer wrote a translation of this poem, of which we have only a fragment, and similar allegorical figures appear in several of his dream vision poems, particularly in the prologue of the Legend of Good Women, where a daisy figures prominently as the representation of the faithful Alceste and several of the allegorical figures from the Roman de la Rose are mentioned. Furthermore, part of the explanation given in the poem for Chaucer’s necessity in writing this poem is because he “hast translated the Romaunce of the Rose”, considered to be a “heresye” against the law of the god of Love (l. 329-330). Interestingly, the “Parlement of Foules” is presented as an example of how Chaucer has assisted Love, and serves as a justification for why the writing of the Legend of Good Women, rather than a more serious punishment, is required of him (l. 415-423).

King’s 322, from which the first image is drawn, is an Italian manuscript of the mid fifteenth century and contains a series of love sonnets written for a Mirabel Zucharia or Zucharina, presumably the woman depicted in the image. Harley 4425, from which the second image is drawn, is a late fifteenth century Netherlandish manuscript in French containing four large miniatures, of which this is the final one. It was originally commissioned for Engelbert II, count of Nassau and Vianden. Bodleian Douce 195, from which the third image is drawn, is richly illustrated with one hundred and twenty five miniatures. Originally produced in France, it was owned by Louise of Savoy, the wife of Charles of Orléans and mother of the French king Francis I.

Valentine's Day.

Seth Mulliken

14

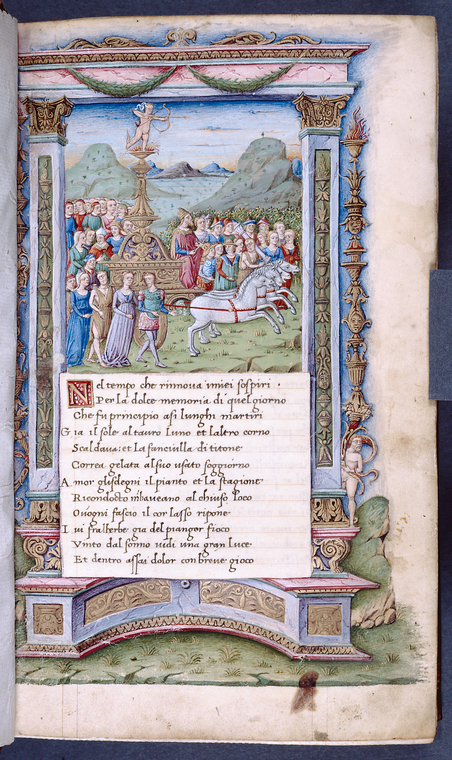

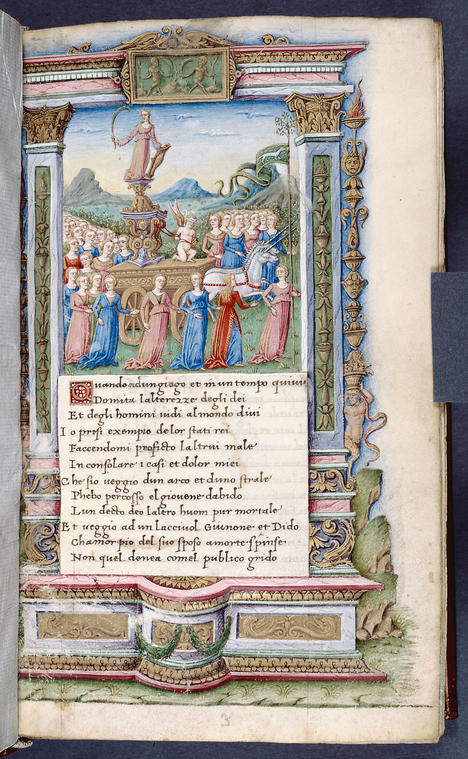

Chaucer, his contemporaries, and the authors of the Roman de la Rose were not the only individuals to write about love in the middle ages. Petrarch—whose sonnets regarding his muse, “Laura,” would come to represent the medieval ideal of beauty—also wrote a series of Triumphs in five parts. First, Love triumphs over Man, then Chastity triumphs over Love. Death triumphs over Chastity, and Fame over Death. Time triumphs over Fame, and finally Eternity over Time. The first two images here depict the first two triumphs, with carts drawing allegorical representations of both Love and Chastity. The third image, from Harley 3567 (f. 9r), of Petrarch and Laura, with Love – represented as we would expect today and as he’s depicted in the first Triumph – aiming his arrow at her. Note Laura’s fair skin and blond hair, which would come to be part of what is known as the Petrarchan ideal.

While it is not known if Chaucer ever met Petrarch, he was influenced in his later works by Italian humanism. He was part of a diplomatic envoy to Italy in 1372, and the framing device of his most famous work, the Canterbury Tales, is taken in part from Boccaccio’s Decameron. Likewise his Troilus and Criseyde is a translation and adaptation of Boccaccio’s version in his Il Filostrato. It is one of the pieces of evidence given to require him to write the Legend of Good Women, and it is likely that Chaucer read Petrarch’s set of Triumphs even if the two never met.

Petrarch himself is mentioned in Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale, where the Clerk-as-narrator states that the tale he is about to tell was learned by him from Petrarch at Padua (l. 26-31). The Clerk’s tale, that of patient Griselda, is taken from Petrarch’s translation of Boccacio’s Griselda and, much like the tales from the Legend of Good Women, serves to show faithful love as a counterpoint to the misogynistic undertones of the Roman de la Rose or the faithlessness of Troilus and Criseyde.

While it is not known if Chaucer ever met Petrarch, he was influenced in his later works by Italian humanism. He was part of a diplomatic envoy to Italy in 1372, and the framing device of his most famous work, the Canterbury Tales, is taken in part from Boccaccio’s Decameron. Likewise his Troilus and Criseyde is a translation and adaptation of Boccaccio’s version in his Il Filostrato. It is one of the pieces of evidence given to require him to write the Legend of Good Women, and it is likely that Chaucer read Petrarch’s set of Triumphs even if the two never met.

Petrarch himself is mentioned in Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale, where the Clerk-as-narrator states that the tale he is about to tell was learned by him from Petrarch at Padua (l. 26-31). The Clerk’s tale, that of patient Griselda, is taken from Petrarch’s translation of Boccacio’s Griselda and, much like the tales from the Legend of Good Women, serves to show faithful love as a counterpoint to the misogynistic undertones of the Roman de la Rose or the faithlessness of Troilus and Criseyde.

Valentine's Day.

Seth Mulliken

15

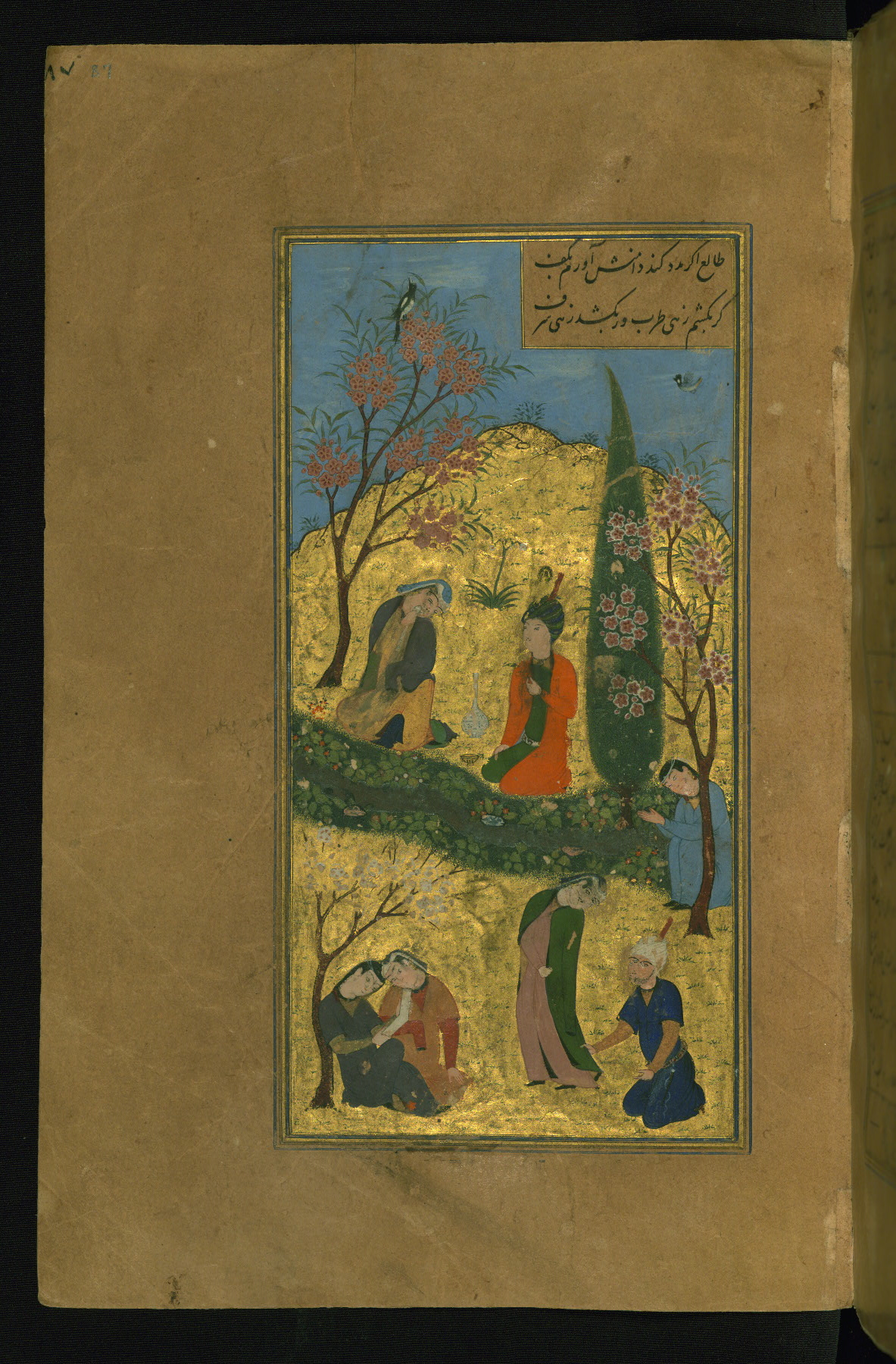

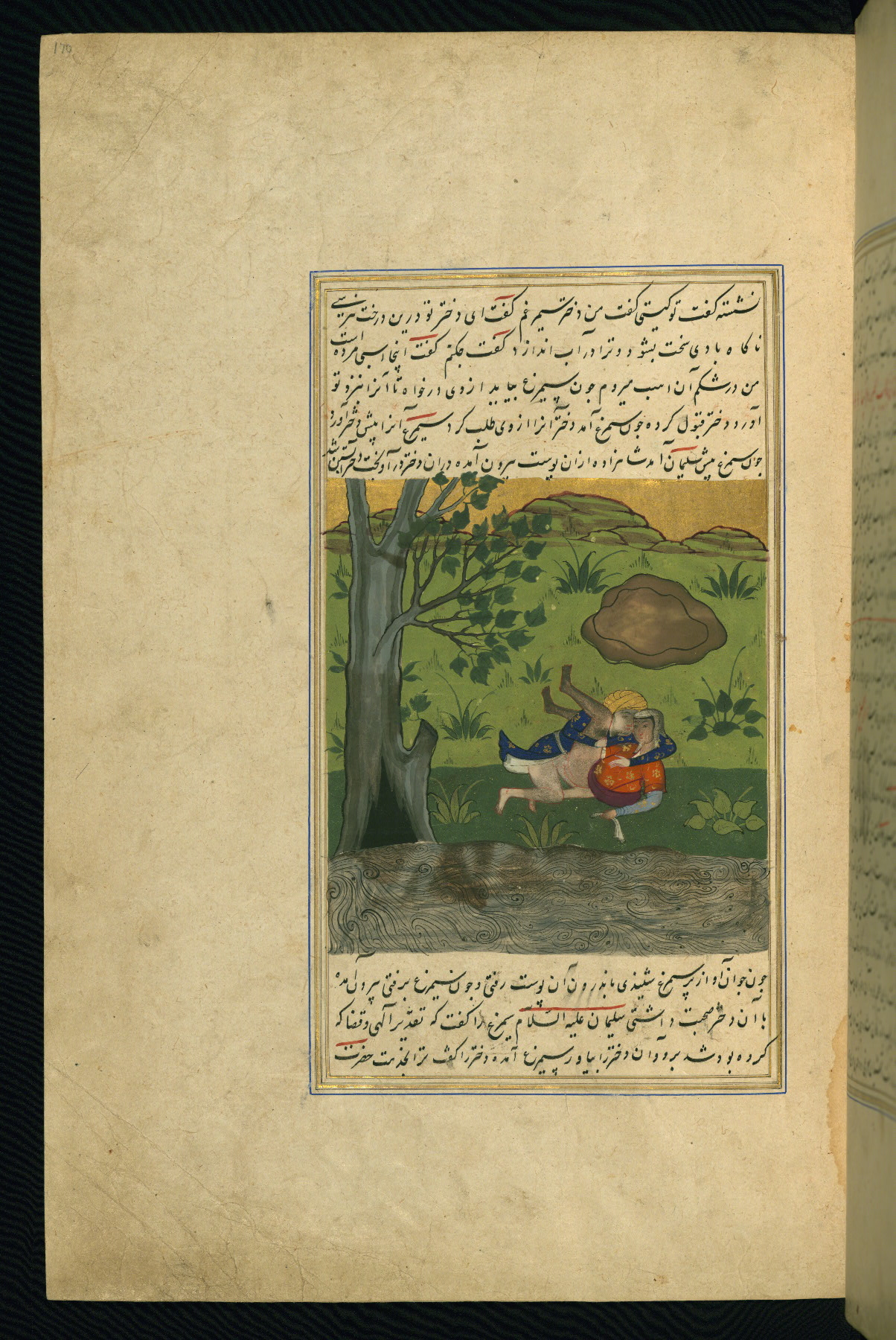

Finally, for our last three items we’d like to show you some depictions of the more carnal side of love. The first of these items, from the copy of the Roman de la Rose in BNF Francais 25526 (f.l06v), depicts a nun harvesting phalli from a tree. On the right side of the image she is shown embracing a monk, indicating her reason for such hard work in harvesting! Likewise, the second image, from Walters 628, shows altogether more chaste couples engaging in various acts of courtship by a river. This manuscript is particularly interesting because it shows that ideas of courtship and love depicted in western European manuscripts often had analogues from the Islamic world. There is even an analogue of the bawdy embrace from BNF Francais 25526 in Walters 593 in the final image, although it goes much further and is not coy about depicting the lovers mid-coitus!

And with that, we at MESA wish you and yours a happy Valentine’s day in whatever mode you may choose to celebrate.

And with that, we at MESA wish you and yours a happy Valentine’s day in whatever mode you may choose to celebrate.

Valentine's Day.

Seth Mulliken

Endnotes

1 "Valentine, n.". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 11 February 2014 http://www.oed.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/view/Entry/221141?rskey=kh1Liy&result=1&isAdvanced=false. For further information on the connection between Chaucer and Valentine’s Day, see Henry Ansgar Kelly’s Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine (Leiden: Brill, 1986).

Links

No links