The Genesis of a Medieval Manuscript

lquigley

«Previous page

•Page 1

•Page 2

•Page 3

•Page 4

•Page 5

•Page 6

•Page 7

•Page 8

•Page 9

•Page 10

•Page 11

•Page 12

•Page 13

•Page 14

•Page 15

•Page 16

You are here •Page 17 •Page 18 •Page 19 •Page 20 •Page 21 •Page 22 ♦Endnotes »Next page

You are here •Page 17 •Page 18 •Page 19 •Page 20 •Page 21 •Page 22 ♦Endnotes »Next page

108

|

|

Glossing

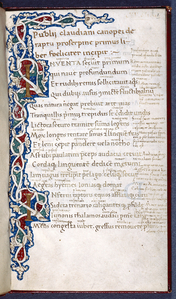

While some glosses were added long after the manuscript was completed, most were added before the binding process, copied directly from another manuscript along with the main body of the text itself. In many instances, both the glosses and the main text were drawn from the exemplar; in others, however, the glosses could be added from other relevant sources at the time of transcription and correction (Graham and Clemens 39). While early glosses tended toward simplicity, offering only basic explanations for words and phrases, later glosses became more complex, offering more information on arcane subjects as well as author opinions. As glosses, changed, so too did the methods with which they were applied to manuscripts. Early, simple glosses could often be added "in the interline directly above the textual element to which they related" (Graham and Clemens 39). The scribe would frequently use a smaller form of print to insert the gloss, in order to avoid crowding the main text. These simple glosses came in two general forms: the lexical gloss and the suppletive gloss. Lexical glosses "supplied one or more synonyms for difficult words or phrases in the main text," and generally began "with the abbreviation .i. for id est" (Graham and Clemens 39). Suppletive glosses, on the other hand, provided words or phrases not included in the main text. Latin texts, for example, often omitted the verb to be; a suppletive gloss would have added "the verb in its appropriate tense and person" (Graham and Clemens 39). Longer glosses would be entered in the margins and linked to the relevant text by a pair of signes-de-renvoi. As glosses grew longer and more complex, scribes adjusted the construction of the page itself. Margins grew wider, and the page would be ruled to receive "both main text and gloss" (Graham and Clemens 40). In these instances, the transcribing scribe would write both the main text and the glossing at the time of transcription, copying it directly from the exemplar. Bibles were among the most heavily glossed texts; also included in this, however, were legal texts, the Sentences of Peter Lombard, and all the works of Aristotle (Graham and Clemens 40). With the addition of glossing, the manuscript would be ready for binding. |

|